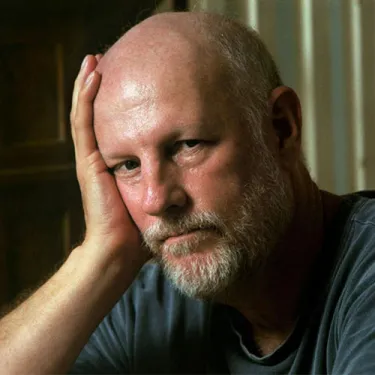

Doug Anderson

Visiting Poet

Doug Anderson served in the Vietnam war and his poems reflect the horrors, tragedies, and unlikely friendships of that tragic time. Upon returning home, Anderson earned his M.A. from the University of Arizona, and then settled in Northampton, where he began to write plays and poems in a workshop with Jack Gilbert. A meticulous, unerring chronicler, especially of his experiences in Vietnam, Anderson has published three volumes, including The Moon Reflected Fire, winner of the 1995 Kate Tufts Discovery Award. Joyce Peseroff writes that this work is “not just about Vietnam but resonant with the history of warriors from the backyard to The Iliad to the Bible.

Anderson’s subsequent collection, Blues for Unemployed Secret Police, was funded by a grant from The Eric Matthieu King Fund of the Academy of American Poets, and praised by Booklist for its “powerful, funny-horrific, brutal-tender poems.” His recent poetry and prose have been published in Ploughshares, the Connecticut Review and The Autumn House Anthology of American Poetry, as well as this year’s Contemporary American War Poetry. Recipient of a Pushcart Prize, an NEA grant, and a Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship, Anderson teaches at the University of Connecticut and the William Joiner Center for the Study of War and Its Social Consequences. He is currently at work on a memoir, Don’t Rub Your Eyes, about Vietnam and the nineteen-sixties.

Select Poems

We cross the bridge, quietly.

The bathing girl does not see us

till we’ve stopped and gaped like fools.

There are no catcalls, whoops,

none of the things that soldiers do;

the most stupid of us is silent, rapt.

She might be fourteen or twenty,

sunk thigh deep in the green water,

her woman’s pelt a glistening corkscrew,

a wonder, a wonder she is; I forgot.

For a moment we all hold the same thought,

that there is life in life and war is shit.

For a song we’d all go to the mountains,

eat pineapples, drink goat’s milk,

find a girl like this, who cares

her teeth are stained with betel nut,

her hands as hard as feet.

If I can live another month its over,

and so we think a single thought,

a bell’s resonance.

And then she turns and sees us there,

sinks in the water, eyes full of hate;

the trance broken.

We move into the village on the other side.

From THE MOON REFLECTED FIRE (Alice James, 1994)

In Taiwan, a child washes me in a tub

as if I were hers.

At fifteen she has tried to conceal

her age with makeup, says her name is Cher.

Across the room,

her dresser has become an altar.

Looming largest,

photos of her three children, one black,

one with green eyes, one she still nurses,

then a row of red votive candles, and in front,

a Buddha, a Christ, a Mary.

She holds my face to her breasts, rocks me.

There is blood still under my fingernails

from the last man who died in my arms.

I press her nipple in my lips,

feel a warm stream of sweetness.

I want to be this child’s child.

I will sleep for the first time in days.

From THE MOON REFLECTED FIRE (Alice James, 1994)

Love won’t behave. I’ve tried

all my life to keep it chained up.

Especially after I gave up pleading.

I don’t mean the woman,

but the love itself. Truth is,

I don’t know where it comes from,

why it comes, or where it goes.

It either leaves me feeling the knife

of my first breath

or hang-dog and sick

at someone else’s unstoppable

and as the blues song says,

can’t sit down, stand up, lay down pain.

Right now I want it.

I’m like a country who can’t remember the last war.

Well, that’s not strictly true.

It’s just been too long.

Too long and my heart is like

a house for sale in a lot full of high weeds.

I want to go down to New Orleans

and find the Santeria woman

who will light a whole table full of candles

and moan things, place a cigar

and a shot of whiskey in front of Chango’s picture

and kiss the blue dead Jesus on the wall.

I want something.

Used to be I’d get a bottle

and drink until the lights went out

but now I carry my pain around everywhere I go

because I’m afraid

I might put it down somewhere and lose it.

I’ve grown tender about my mileage.

My teeth are like stonehenge and my tongue

is like an old druid fallen in a ditch.

A soul is like a shrimper’s net they never haul up

and it’s full of everything:

A tire. A shark. An old harpoon.

A kid’s plastic bucket.

An empty half-pint.

A broken guitar string.

A pair of ballerina’s shoes with the ribbons tangled

in an anchor chain.

And the net gets heavier until the boat

starts to go down with it and you say,

God, what is going on.

In this condition I say love is a good thing.

I’m ready to capsize.

I can’t even see the shoreline.

I haven’t seen a seagull in three days.

I’m ready to drink salt water,

go overboard and start swimming.

Suffice it to say I want to get in the bathtub

with the Santeria woman and steam myself pure again.

The priest that blesses the water may be bored.

Hung over. He may not even bless it,

just tell people he did. It doesn’t matter.

What the Santeria woman puts on it with her mind

makes it like a holy mirror.

You can float a shrimp boat on it.

The spark that jumps between her mind

and the priest’s empty act

is what makes the whole thing light up

like an oilslick on fire against a sunset over Oaxaca.

So if I just step out into it.

If I just step off the high dive over a pool

that may or may not have water in it;

that act is enough

to connect the two poles of something

and make a long blue arc.

I don’t have a clue about any of this.

Come on over here and love me.

I used to say that drunk.

Now I am stark raving sober

and I say, Come on over here and love me.

From THE MOON REFLECTED FIRE (Alice James, 1994)