War, Family, and the Divides We Carry

Smith Quarterly

Đoan Hoàng Curtis ’94 reflects on the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon

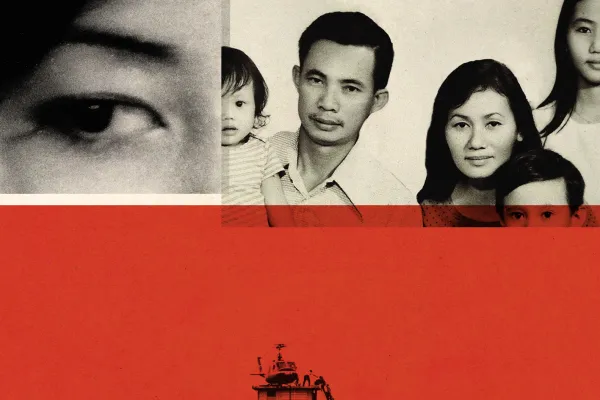

Illustration by Vanessa Saba

Published April 25, 2025

Fifty years ago—on April 30, 1975, when I was 3 years old—my parents, my 6-year-old brother, and I were airlifted out of Saigon on the last U.S. helicopter taking civilians in the final hours of the Vietnam War.

Just minutes before, I had been in a vehicle with my father, brother, and mother, who was pregnant with my younger sister, while my 17-year-old sister and teenage aunt and uncle followed us on scooters. My father was a South Vietnamese Air Force major, and our home at the base had been shelled. We were searching for another place to stay but were soon caught up in the chaos that became the fall of Saigon. My older sister became separated from us. My parents suddenly understood that we had to leave the country immediately.

My sister was later imprisoned by the communists who rolled into Saigon that day in tanks. We would not see her for six years, when, having been released from prison, she escaped Vietnam by boat.

The fear and trauma of watching our country collapse will be with each of us for the rest of our lives. I remember our peaceful home, the faces of those I loved, and the colorful markets—then, later, the refugee camps and arriving in Kentucky. But my memories of the week we escaped are in the form of phobias: helicopters, large ships, and loud crowds.

I have spent most of my life making films and writing about the Vietnam War: I wrote my first family biography at age 10 and created my first documentary at 12. My papers at Smith focused on the war—specifically, comparing the media’s account of the war with my family’s oral histories.

In 2007, I directed and produced the documentary film Oh, Saigon: A War in the Family. My latest work is as a producer on the documentary series Turning Point: The Vietnam War, which premiered on Netflix on April 30—the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon.

My father, who had trained as a pilot in Texas, was fiercely anti-communist, teaching me to hate the Viet Cong (Vietnamese communists) from a young age. To my shock, when I returned to my homeland in 1997, I learned my father had brothers he had never mentioned: Uncle Hai, who fought against my father for communist North Vietnam, and Uncle Dzung, who was anti-war. Although the three brothers had many overlapping opinions about an independent Vietnam, they were forced to choose an ideology, molding their more complex beliefs into those of their political sides.

While making Oh, Saigon, I became close to my uncles. I learned that at 15, Uncle Hai had joined the communist Viet Minh’s fight for independence from France and was part of the historic victory at the 1954 Battle of Dien Bien Phu. After the French withdrew, Vietnam was divided at the 17th parallel into two countries: the pro-democracy Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) and the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam). By the time my father was 15, his country—South Vietnam—was defending itself from communist attacks. Uncle Hai fought against my father. In the later 1960s, when Uncle Dzung was 15, the anti-war movement was in full swing, and he shot his own hand to avoid fighting for South Vietnam. The political decisions made by my father and his brothers were defined by world events that happened during their coming of age, and they ended up choosing politics over family relationships.

For the Netflix series, we filmed Americans, North Vietnamese, and South Vietnamese. This brought me deep into the stories of people I had been told were my enemies. One day, I heard one side; the next day, the flip side. I found myself both enthralled and confused by each story I heard as it became clear to me how a conflict escalates. The two Vietnamese sides feared domination; America feared the spread of communism. For many, fear and a sense of victimhood together are the common tipping points into taking violent action.

Filming in Ho Chi Minh City, formerly Saigon, I met Võ Thi Trong. As a girl, she was concerned about why the young American soldiers who slept in foxholes nearby wept at night. But when she was orphaned by American artillery, Trong joined the Viet Cong and, as a teenager, proudly set off a bomb that killed 15 Americans in a café. She ended up in a South Vietnamese prison, where she was severely beaten and sustained a broken arm. After developing gangrene, she was sent to a South Vietnamese hospital, where her arm was amputated at the elbow. “Even though they knew I was the enemy,” she remembers, “these strangers still fed and cared for me.” Trong embodies the paradoxes of war, switching between seeing the humanity and inhumanity of others.

One person’s righteous revenge is another’s devastation. Scott Camil, a U.S. Marine during the war, made a conscious decision to kill as many Vietnamese as he could in retaliation for the death of his friend in a Viet Cong bombing. Like Trong, he was impelled to play a role in a system he didn’t always agree with, fueled by personal fear, anger, and revenge. Camil later testified to Congress as a “Winter Soldier”—military personnel who exposed the war crimes of U.S. troops against Vietnamese civilians. He attested to carrying out orders to commit atrocities by shooting women and children indiscriminately.

Trong and Camil both felt angry that their loved ones were killed by the “enemy.” Both wanted revenge. This desire to lean into one’s natural feelings of anger to the point of committing violence creates a cycle of continued violence.

That my dad and his brothers fought each other during the war but ultimately made peace showed me that love and humanity are more powerful than political parties. I have found myself at political odds with those in the second generation of my family. My brother and cousin stunned me when they marched on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, feeling victimized by what they saw as a “stolen election.” They are surprisingly anti-immigrant. My brother believes in QAnon conspiracy theories and loves Donald Trump’s anti-Chinese rhetoric. Like many South Vietnamese, he and my sister blame and fear the communists for the loss of our home and country. Their support of Trump is based on their belief that he and the Republican Party are as anti-communist as they are. They fear communism more than anything.

Uncle Hai died just before Oh, Saigon was released on PBS. My father experienced terrible grief, having only gotten to see his brother twice after 59 years of separation. He was never able to heal from the loss of his family and country, and the isolation that division brings. When my father died, I tried to see my sister, brother, and cousin through more compassionate eyes.

Now, I look at the next generation of my family. I see them caught in the crossfire of our current political divisions in America. I don’t want them to endure what I did, witnessing the division of their family and the destruction of their country over ideology. We suffered many deaths and horrors in the Vietnam War, which was the culmination of people being unable to hear each other. Now, I choose to put the love of family and community first.

To paraphrase Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh: Humans are not the enemy. Our enemies are judgment, righteousness, blame, intolerance, rigidity, superiority, and discrimination—all rooted in fear. When I forget the humanity of people with opposing views, I create a war in myself. I am compelled by the memory of my father and his brothers to disarm and remember to love again.