Toward Our Better Selves

Smith Quarterly

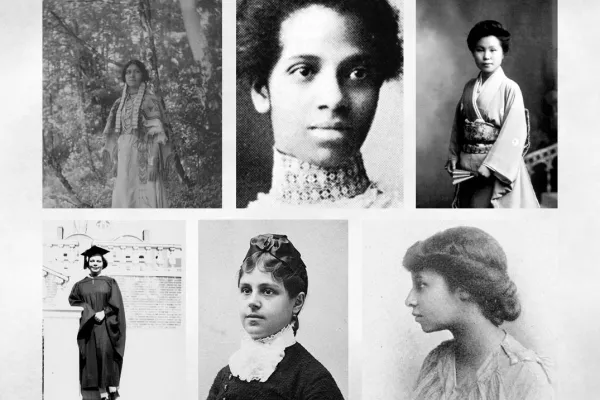

Transformative figures in Smith’s history helped create a more just and inclusive college community

Published August 15, 2025

As vice president for equity and inclusion and as a student of language, I have given much thought to how we might define inclusion. One definition could emphasize conformity—that is, requiring individuals to meet a dominant standard to earn belonging from a central power. We might call this provisional inclusion. Another definition, however, would enable individuals to bring their whole selves into an ecosystem—say, a college—and have their contributions welcomed as a means of changing that ecosystem. We might call this transformative inclusion, which expects that every student, faculty member, and staff member will help shape the institution—not merely assimilate into it.

I’ve seen this kind of inclusion at Smith over my 25-plus-year career. Students’ questions and comments in class influence curricula. Staff members lead initiatives that sustain education outside of the formal classroom. Faculty members create knowledge and art, influence student trajectories, and participate in institutional governance. Transformative inclusion brings out the best in all of us—and the best in the college.

A call for transformation was articulated in 2021 through a strategic plan titled Toward Racial Justice. The plan’s first principle acknowledges: “Because Smith was not originally designed for the diverse students, staff, and faculty that we have now, we are called to reflect on our past and present to build a more just and inclusive future.” This is necessary work that builds on the efforts of early change makers—students, faculty, and staff who challenged exclusion in its many forms.

Smith’s history is rich with stories of individuals who have transformed the college—and the world—in profound ways. Here we pay tribute to some of them.

Salomé Machado 1883:

Smith’s first Latina student. Born in Cuba, she is also considered the first woman from outside the U.S. to be admitted to the college.

Angel De Cora 1896:

Smith’s first Native American student. She went on to become a well-known advocate for Native American rights as well as an influential painter and illustrator.

Otelia Cromwell 1900:

Smith’s first African American graduate. She later received a doctorate from Yale, becoming the first African American woman to do so. Cromwell Day is named for her and her niece Adelaide Cromwell ’40.

Ethel Chesnutt 1901 and Helen Chesnutt 1902:

African American sisters who had to move to multiple off-campus addresses during their time at Smith. After graduating, Ethel worked as an instructor at Tuskegee and later as a social worker for a poverty-relief organization in Washington, D.C. Helen taught Latin for many years and authored a biography of the sisters’ father, the writer Charles Chesnutt.

Tei Ninomiya 1910:

First East Asian student to graduate from Smith. She worked as a teacher in Japan for many years. In 2016, Smith dedicated Ninomiya House in her honor.

Euphemia Lofton Haynes 1914:

First African American woman in the United States to earn a doctorate in mathematics. She helped dismantle racial discrimination in the Washington, D.C., school district.

Carrie Lee 1917:

Like the Chesnutt sisters, Lee faced racial discrimination in housing upon arrival at Smith. With support from her father and Otelia Cromwell, she successfully advocated for on-campus housing. She went on to have a long career as a public school teacher.

Sabiha Hashimy ’37:

Smith’s first Middle Eastern student. Following graduation, she served as principal of Kirch Secondary School for Girls in Baghdad. Hashimy House is named for her.

Adelaide Cromwell ’40:

Otelia Cromwell’s niece. She joined the sociology department as the college’s first Black faculty member in 1945.

Evelyn Boyd Granville ’45:

Second African American woman in the United States to receive a doctorate in mathematics. Her work at NASA helped humans reach the moon.

Yolanda King ’76:

Activist, actress, and author. A daughter of Martin Luther King Jr., she continued her family’s legacy of civil rights advocacy.

Laura Rauscher:

Former director of Smith’s Office of Disability Services and the college’s first senior policy adviser on disability access and inclusion. In 2024, the crew house ramp was named in her memory.

Eleanor (Ellie) Rothman:

Founding director of the Ada Comstock Scholars Program, which has welcomed close to 2,500 nontraditional-age students to Smith since its establishment in 1975.

By persisting in the face of discrimination and racism, these students and scholars, educators and leaders, inspired the college’s ongoing efforts to create systemic change. Last year, Smith honored their legacy by renaming several buildings after Haynes, Lee, Granville, King, and Rothman, recognizing both the breadth of the college’s history and their enduring impact on campus and beyond.

Smith’s journey toward inclusion is ongoing. But we have a map—and the intentionality behind our efforts brings us closer to realizing founder Sophia Smith’s vision that her namesake college be a “perennial blessing to the country and the world.”