Pushing Beyond Gender Boundaries

Smith Quarterly

Smithies have long challenged the idea of what it means to be a woman

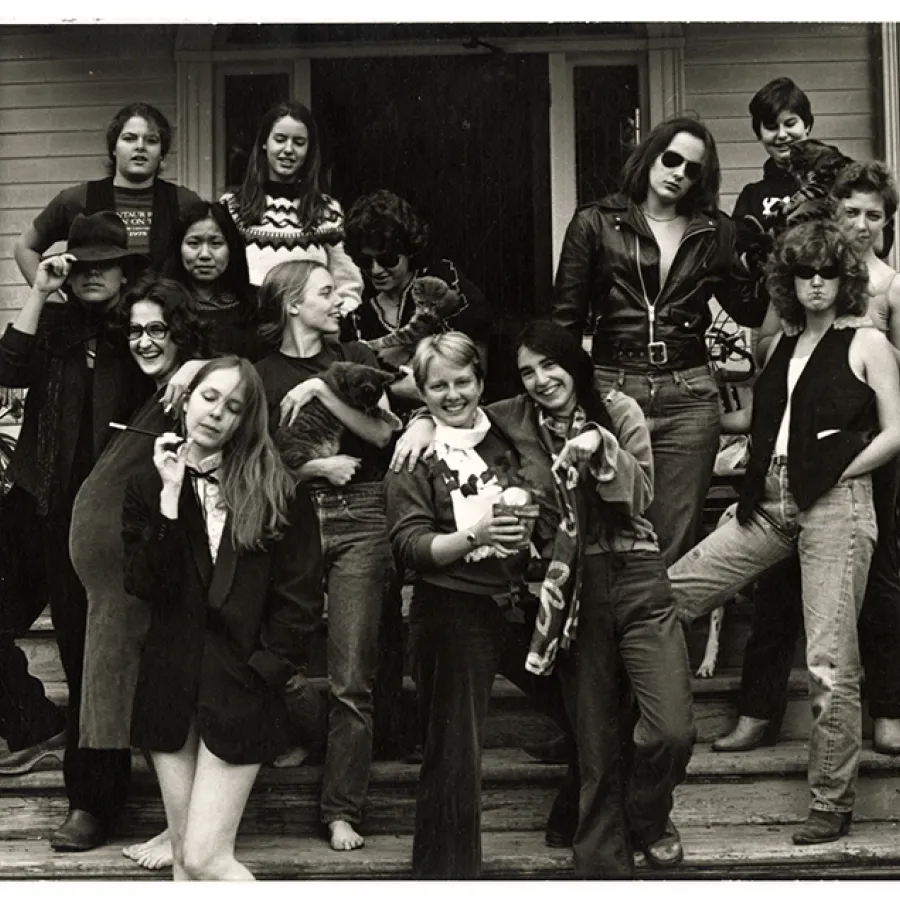

By the 1980s, Hover House—one of Smith’s co-op houses—became known for attracting lesbians. When the college decided to close it, students staged a sit-in outside the president’s office in College Hall.

Photograph courtesy of Smith College Special Collections

Published August 14, 2025

“What is a woman?”

The French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir asked this question more than 75 years ago. In her 1949 book, The Second Sex, de Beauvoir famously argued, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” Throughout the late 19th century, womanhood was narrowly defined by marriage and motherhood. Sophia Smith challenged these ideas with a radical vision: Her namesake college would not be a finishing school for future wives but rather a rigorous academic institution comparable to the likes of Amherst College and Yale University. Women would study science, mathematics, Latin, and Greek. Early Smith students were on the cusp of evolving ideas of gender; they believed women were intellectually just as capable as men. As Tobias Davis ’03, an inclusion education trainer at Smith, said in an interview, “To be a woman and get a college education back in the day was in and of itself an incredible gender transgression.”

At Smith’s founding, debates swirled around the impact of college education on women. In 1873, two years before Smith opened its doors to six faculty members and 14 students, Harvard Medical School professor Edward Clarke published Sex in Education, in which he warned that women who engaged in sustained vigorous mental activity—studying in a “boy’s way”—risked atrophy of the uterus and ovaries, masculinization, sterility, insanity, and even death. Clarke believed that women should study no more than four hours a day and should avoid studying at all while menstruating. Claiming that educated women would develop “monstrous brains and puny bodies,” Clarke advised that women’s energy should be directed to their “reproductive machinery” and not “diverted to the brain by school.” To quell any fears, Smith’s first president, Laurenus Clark Seelye, announced at Smith’s opening in fall 1875, “It is to preserve her womanliness that this College has been founded.”

Seelye had long expressed anxieties about how a traditional college with dorm living might affect women. Comparing women’s education to men’s, he asked, “What if the same climate which strengthens the pine blasts the rose?”

In her 1993 book Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women’s Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s, historian and former Smith professor Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz describes the general concern that women’s colleges would lead to “the creation of a separate women’s culture with its dangerous emotional attachments, its visionary schemes, and its strong-minded stance to the world.” Seelye, Horowitz writes, “had a strong distaste for the professional women” and feared that education would rob them of, in his words, their “amiable qualities.”

For Professor Emerita Susan Van Dyne, this photo of the class of 1883 on the porch of Hubbard House in fall 1880 perfectly encapsulates Smithies’ penchant for resisting traditional gender norms.

Photograph courtesy of Smith College Special Collections

But Seelye and his compatriots had a plan for preventing this from happening: “Educate women in college but keep them symbolically at home.” They would erect a central college building for instruction and surround it with cottages, where students would live in familial settings under the close supervision of faculty and house mothers—the origin of Smith’s house system. Seelye also decided to keep all the classes on the first floor of the main academic building so as not to tax women’s bodies by requiring them to climb stairs.

Despite Seelye’s admonitions, the first Smith students had their own ideas of what it meant to be a “college woman.” In a fascinating essay, “‘Abracadabra’: Intimate Inventions by Early College Women in the United States,” Professor Emerita Susan Van Dyne reveals how the first generation of Smith students created a collective sense of themselves as “college women” at a time when such a thing did not exist. For Van Dyne, the photo at right of the class of 1883 on the porch of Hubbard House in fall 1880 perfectly encapsulates “their bravado in adopting masculine sports despite Seelye’s anxious public silence about their involvement in sports; it testifies to intellectual ambitions in laboratory sciences, mathematics, the organization of clubs, and a penchant for resisting traditional gender expectations. The photo also speaks of female intimacy as the currency of daily life, so naturally assumed that its gestures are almost invisible.” Through their poses, we see these Smithies pushing the boundaries of socially accepted roles for women, experimenting with new ways to be women—new activities, studies, and relationships, challenging narrow gender roles and restrictive ideas of women’s capacities.

“The extraordinary fear of and focus on lesbianism in women’s colleges masks deeper fears of female independence and self-sufficiency.”

Smith students most clearly defied acceptable ideas of womanhood in their enthusiastic participation in competitive athletics. In 1892, physical education teacher Senda Berenson introduced Smithies to basketball, albeit with a set of rules different from those followed by men’s teams. So as not to overexert themselves, Smith players had to remain in one of three assigned zones and were allowed only one bounce of the ball before passing it. Using peach baskets as hoops and wearing royal blue bloomers and long-sleeved blouses, Smith students—first-years versus sophomores—played the first women’s basketball game ever on March 22, 1893, in the Alumnae Gymnasium. The entire college turned out “with class colors and banners waving,” students “cheering and screaming,” reported one student in a letter to her mother. Noticeably absent from the crowd, however, were men, because it was considered inappropriate for men to see women wearing bloomers in public. The first-years triumphed over the sophomores, 5–4. Newspapers covered the match with shocked curiosity. Meanwhile, medical professionals issued dire warnings: “Team athletics unfit women for companionship with men, for marriage, and for motherhood. It makes them old before their time, hard, weary, nervously exhausted, irritable.” Nevertheless, Smithies played on, and basketball soon became a popular game among women of the early 20th century.

Gender bending was also seen in campus social life, including theater productions. For an 1896 performance at Dickinson House, members of a student theater troupe donned pants, ties, and men’s hats as well as mustaches, canes, and rifles. In 1910, students sported suits and mustaches at the “half man” dance at 103 South Street.

In her essay, Van Dyne documents the intense female relationships women developed in the early days of Smith’s history. “Not fully articulated, but passionately felt, same-sex desires emerged from widely shared rituals and intimacies that constitute residential college life.”

By the 1970s, notable feminist alums such as Betty Friedan ’42 and Gloria Steinem ’56 openly challenged expectations that Smithies should center their lives on husbands and children. For example, when Steinem gave the keynote address at Commencement in 1971, she called for the repeal of all laws restricting abortion and contraception, leading some parents to walk out. “Not everyone should be a parent any more than everyone with vocal cords should be an opera singer,” Steinem said.

Members of the class of 1897—Grace Kelley, Therina Townsend, H. Louise Peloubet, Albertine Flershem, Katherine Lahm, and Josephine Sewall—get in costume to perform in the Dickinson House production of The Amazons in January 1896.

Photograph courtesy of Smith College Special Collections

At the same time, Smithies began openly expressing their lesbian identities. The college’s first lesbian alliance was founded in the mid-1970s. By the 1980s, Hover House—one of Smith’s co-op houses—became known for attracting lesbians. When the college decided to close it, students staged a sit-in outside the president’s office in College Hall. Following the publication of a 1991 Los Angeles Times article about lesbianism at women’s colleges, then-Smith President Mary Maples Dunn commented, “I think the extraordinary fear of and focus on lesbianism in women’s colleges masks deeper fears of female independence and self-sufficiency.”

Smith’s curriculum also evolved, bringing new ideas about sex, gender, and the critical roles women played throughout history into the classroom. In 1942, Margaret Storrs Grierson 1922, a Smith professor and archivist, established what later became the Sophia Smith Collection—now the oldest repository of women’s history archives in the United States and abroad. At a time when women’s history was not yet a field of study in the academy, Smith valued women’s lives and experiences enough to collect primary sources about them that have formed the basis of so much fascinating scholarship today. In the 1980s, Smith professors Marilyn Schuster, Susan Van Dyne, Martha Acklesberg, and others braved intense headwinds to establish the women’s studies program, which later expanded to incorporate gender and sexuality studies. Smith also embraced disciplines in which women were historically underrepresented, including computer science, engineering, and data sciences.

Today, students are challenging gender norms in new ways. “There have always been trans and nonbinary Smithies, and there always will be; it’s just that now we have the language for ourselves,” says Tobias Davis, who points to a “proud tradition of historically women’s colleges being spaces for those of us marginalized by the cisheteropatriarchy to find our voices and achieve education.” Smith now welcomes applications from students who self-identify as women. On campus, Smithies express a wide range of gender identities. Many students don’t think of gender as a binary but as a spectrum of genders, including nonbinary people and gender-nonconforming people.

From the initial idea of the “college woman” in the late 19th century to the more fluid concepts of gender today, Smith has always been a gender-transgressive place. Conservative critics of the 19th century were right: Women’s colleges did transform women. Smith nurtured explorations of what it could mean to be a woman, challenging narrow and traditional notions of womanhood and gender expression. Smithies pushed against the boundaries of acceptable gendered behavior in what they studied, their physical activities, their relationships to each other, and their identities. By allowing this exploration, however begrudgingly, the college opened the door to new possibilities for Smith students.

Carrie N. Baker is the Sylvia Dlugasch Bauman Professor of American Studies and chair of the Program for the Study of Women, Gender & Sexuality. Her latest book is Abortion Pills: U.S. History and Politics (Amherst College Press).

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of the Smith Quarterly.