Mapping Activism & Justice

Heather Rosenfeld, director of the Spatial Analysis Lab, talks projects and passions

Published December 3, 2024

Heather Rosenfeld, Director of Smith’s Spatial Analysis Laboratory (SAL), has built her life around maps. As an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, she took her first GIS classes, which led to her first job after college, with the Environmental Protection Agency in Chicago, mapping formerly contaminated sites as part of the Superfund project. She also made maps as part of her activism work with a community-based environmental justice organization. It’s not surprising then that her next step was graduate school in human geography at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. During her time there, she studied green technology, worked on a big collaborative mapping project on the transnational hazardous waste trade, and wrote a dissertation on an unusual subject: chicken sanctuaries.

Rosenfeld notes that while most people are familiar with sanctuaries for domestic animals, farm animal sanctuaries are less widely known. They describe the sanctuaries as “trying to transform the institutions of animal agriculture by saying that animals should not be commodities.” Once the animals have been rescued and brought to the sanctuary, the question becomes, “How do we take care of farmed animals when we’re not raising them for resources?” Rosenfeld observes that even at farmed animal sanctuaries, chickens are “the most socially marginal,” which is why they focused on them in particular. In their dissertation entitled Winging It: Rehabilitating Animals, Rehabilitating Animality at Chicken Sanctuaries, Rosenfeld analyzed chicken sanctuary networks and the creation of “alternate societies with humans and non-humans” and mapped their history and rise. They note that while they did literally map the sanctuaries in the US, their interest for this project was more in “mapping as visual storytelling, rather than mapping as quantitative analysis.”

What Rosenfeld loves about maps is the “combination of the technical aspects... and the creativity, the world-making” that mapping both allows and offers. “When I’m teaching mapping classes, we talk about how maps don't just describe places,” she says. “They describe particular perspectives on a place, and then they also influence the places that they're describing. By saying, ‘Okay, this is where the border of a place is,‘ that’s a description and a claim at the same time.”

When Rosenfeld finished their Ph.D. in 2019, they desired a career where they could do meaningful work that centered social change and “social and environmental and multi-species justice” while also allowing them to continue doing research and making the maps they love. Their quest first led them to Tufts, where they worked as both a geography lecturer and a researcher in the MGGG Redistricting Lab, which uses data science to help fight gerrymandering and offers a participatory alternative to partisan-drawn political districts. Then, they came to Smith as a lecturer in environmental geography.

In her three years as a lecturer, Rosenfeld was connected to the SAL through her courses in cartography and environmental research methods. She was drawn to the director position by the combination of continued student contact as well as increased collaboration with faculty members. The SAL has been part of the Center for the Environment, Ecological Design, and Sustainability (CEEDS) since 2022, so there was also the draw of the “awesome” staff of both the SAL and CEEDS, including Kala’i Ellis, SAL’s spatial data analyst and SAL’s student associates, whose work ranges from curricular support to testing materials to helping manage the SAL’s drone collection.

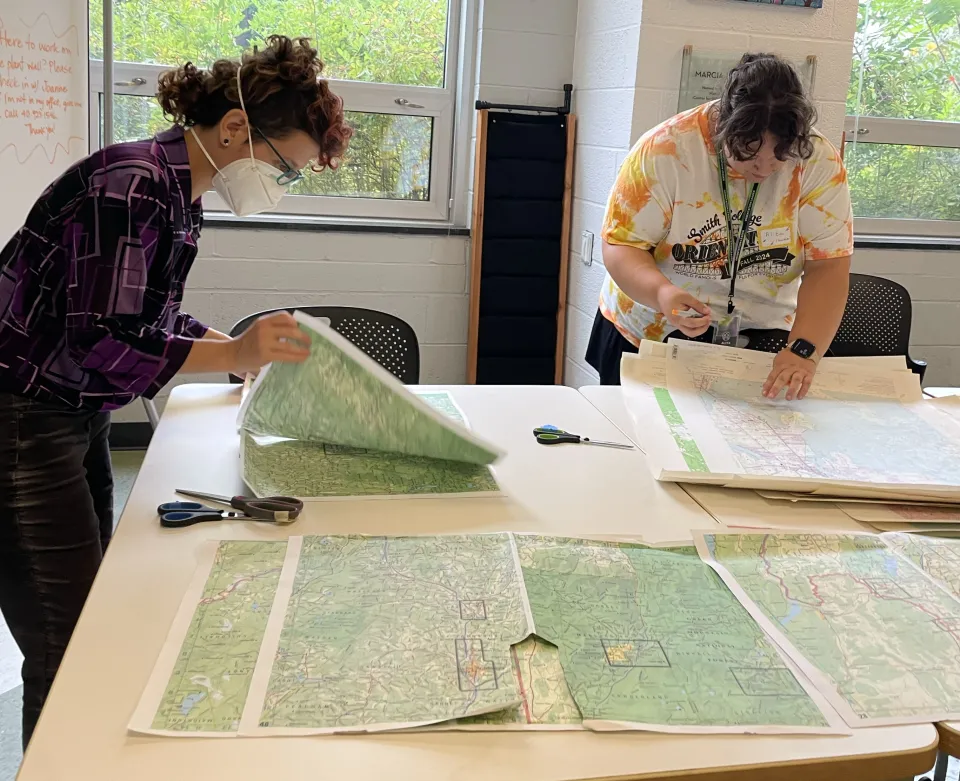

Heather Rosenfeld, left, works with a student orientation leader to make buttons out of maps for an Orientation event centered around sense of place.

In the 2023–24 academic year, more than 500 students, faculty and staff used the resources of the SAL. While the largest number of students come from the departments of geosciences and environmental science and policy, students in the humanities use the SAL as well. Humanities students often opt to learn narrative mapping through a program called Story Maps, which allows students to create a web-based narrative with images, text and interactive maps, giving them a visual way to present information. Students have documented their study abroad experiences through StoryMaps, for example, and recently a class used the program to study how specific artifacts have moved through museum collections around the world.

As Rosenfeld settles into their new position, they are interested in building on the present strengths of the SAL as well as making some forays in new directions. They are hoping to support more interdisciplinary projects and to build up connections with places around campus such as the Kahn Institute and the Smith College Museum of Art, along with more departments in the humanities and social sciences. They are also interested in eventually expanding the SAL’s commitment to community-based work. Over time, they hope that the SAL can develop partnerships in the community that would give Smith students new opportunities to do “tangible, meaningful work.” For example, one of Rosenfeld’s Smith classes partnered with Climate Action Now to “map the environmental justice impacts of a proposed pipeline in Springfield,” and Climate Action Now is using the maps as part of their work, which Rosenfeld describes as “amazing.”

Another longer-term goal is to use mapping to promote accessibility on campus. One project, with Shiya Cao, MassMutual Assistant Professor of Statistical and Data Sciences, involves using a participatory process to map both accessible and inaccessible spaces. Another project is on accessible cartography. She describes this as a “slow-moving research project” but something that she now integrates into the cartography lessons she teaches and hopes to expand on over time. Rosenfeld adds that the SAL is also looking to focus more on 3D and tactile mapping, which would involve creating topographical maps that actually show elevation. Creating a 3D map of the MacLeish Field Station will be the first project of this sort.

In their three plus years at Smith, as a lecturer and now as director of the SAL, Rosenfeld is most grateful for the people: “Getting to work with folks who care about... concretely making the world better and more just, and redressing some of the harms of past and current generations in terms of social and environmental justice, in terms of accessibility, in terms of inclusion, in terms of liberation... Being part of that is a big thing.”