‘Light in Times of Darkness’

Smith Quarterly

Reflecting on a difficult chapter in Smith’s history

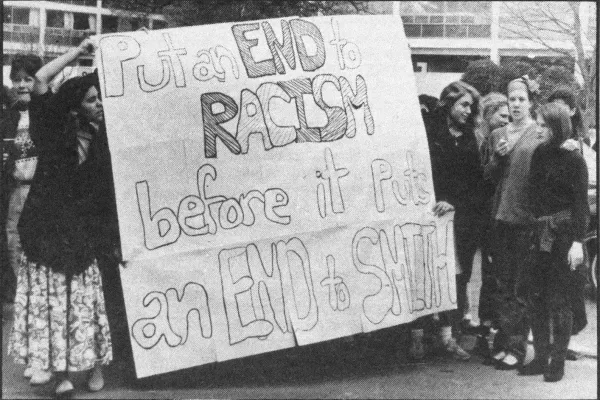

On May 4, 1989, The Sophian published a special edition on racial tension at Smith. In this above-the-fold photograph, students protest racist notes sent to Black residents of Chapin House.

Published August 18, 2025

My college years unfolded during a dramatic period of student activism at Smith and on campuses nationwide, driven largely by reactions to affirmative action and responses to widespread incidents of hate, racism, and prejudice. A May 1989 New York Times headline captured the climate: “Deep Racial Divisions Persist in New Generations at College.”

Even before arriving at Smith, I remember reading about massive protests around divestment, including the takeover of College Hall in the mid-1980s. My fellow first-years and I knew that the Smith students who came before us had succeeded in their demands for divestment and had fostered a new campus ethos of awareness around equality and diversity. As I set off for Northampton, I couldn’t have foreseen how my own experience at Smith would ultimately shape my development as a leader and advocate, instilling in me a lifelong commitment to public service. Now, as I revisit articles from my days at Smith and reflect on the issues of that era, I am struck by the need to view the student engagement happening on campuses today through the lens of what we experienced 30-plus years ago. What lessons should we draw, and what might unfulfilled solutions to racism and prejudice mean for Gen Z, Gen Alpha, and beyond?

Being “culturally aware” and creating a campus where all members of the community felt welcome were persistent themes during my first three years at Smith. The Sophian’s fall 1986 issue ran an interview with Kelly Gerald ’87—president of the Student Government Association (SGA) at the time—in which she was asked, “Do you think there is a need to seek the concerns of minority and nonminority students in recognition of diversity on campus?” Gerald responded, “When you come to a school like Smith, you’re put into the position of learning about a larger society.” That sentiment extended to the college’s administration as well. Then-President Mary Maples Dunn had begun work on a larger diversity program that included contributions from students on how to build a more diverse student body, faculty, staff, and leadership team. By the time I was a junior, several significant institutional changes had taken place, including the creation of an affirmative action officer position in October 1989, the adoption of what was called the Smith Design for Affirmative Action and Institutional Diversity, and a $30,000 fund to “broaden the curriculum to incorporate world and American cultures.”

Though progress was happening at the institutional level, the campus environment was tense due to racial conflicts and general unease. Almost every issue of The Sophian during my junior year included stories on issues related to race, identity, and equality. One article proclaimed, “Racism continues to plague the Smith College community.” The Mwangi Cultural Center was one of the only places on campus explicitly designed as a private space for cultural groups. Even that center was a source of tension as different student groups vied for use of the space, creating unhealthy and complex relationships across cultural groups and identities.

Pandith delivers her Convocation speech in fall 1989. She was focused on uniting the Smith community, which had been riven by racial strife.

Photograph courtesy of the author

Amid the turmoil, there was a steady focus on how to develop solutions and bring about change. Respect and celebrating a diverse campus were key themes of weekly house meetings, in the SGA senate, and within student clubs and organizations. But it was the discovery of a series of racially charged notes delivered to students that caused the campus to erupt. Two weeks after I was elected SGA president in spring 1989, at least six anonymous harassing notes were sent to students. But it was four notes enclosed in an envelope addressed to Black students in Chapin House that tore apart the campus’s already delicate seams. Though antisemitic, anti-white, and homophobic notes had been discovered throughout the year, the Chapin House incident was considered the final straw, and students responded with candlelight vigils, in-house discussions, and a six-hour meeting in Chapin intended to get a confession out of whoever wrote the notes. (No one stepped forward.) President Dunn ultimately handed the Chapin notes over to the district attorney’s office and summoned the FBI to investigate. As tensions rose, she called a mandatory all-college meeting in John M. Greene Hall (JMG).

Thirty-six years later, I can still feel the emotion and pain of that meeting. As SGA president, I was asked to join members of the administration onstage, but I chose to sit with my peers in the audience and come up to the stage when called—a visible symbol of my support of and connection to my fellow students. From the start, the air in JMG was heavy with tension and anger. Students were hissing and stomping and yelling. I recall being speechless after a student screamed at me from the audience: “How would you know what it feels like to be a minority? You are white!” In fact, I was born in India, grew up in Massachusetts, and am a Muslim. The source of most of the tension was a call by a student for an immediate vote on a set of demands put forth by various cultural organizations at Smith. The demands were said to be “vital to women of color” on campus. The problem was that the presentation of the demands had not followed established protocol. Ideally, the request would have been read during the JMG meeting and then given to the Committee on Academic Policy. Instead, by calling for an on-the-spot hand vote so that everyone in JMG could see who did and didn’t support the demands, the proposed vote became, in many ways, a dare—and students knew that.

“Learning how to disagree and find ways to hear one another—even when it was painful—took practice, but it was worth the effort. That is not to say that we fixed everything.”

The scene in JMG spiraled deeper into chaos, with groups of students yelling and lobbing ugly accusations at one another; it was raw, emotional, and fierce. At one point, I looked over at the newly elected SGA cabinet members, who were sitting wide-eyed in the front row, clearly disturbed by what was unfolding. I took a step forward and told everyone assembled that we couldn’t have a hand vote—“not in this way.” E. Shelton Burden, the college’s newly appointed affirmative action officer, reinforced the need to follow parliamentary order. The JMG meeting ended with lots of unresolved feelings of anger, frustration, and disappointment among students. In the meantime, the racial strife became a national story, with the JMG event appearing on newscasts across the country. Later that night, Burden told me that this had been my “trial by fire” as the new SGA president.

The next day, the SGA senate and cabinet endorsed a campuswide vote on the six demands—including that a class on racism be added to the curriculum—with a majority of students ultimately supporting them. Though the vote was nonbinding, it sent a message to the college’s administration that progress was not happening fast enough and that more needed to be done to increase diversity and make the campus more culturally aware.

By the end of the 1988–89 academic year, several efforts were underway to repair the social fabric on campus. So when I returned to campus in fall 1989, I knew that as SGA president I needed to address issues related to diversity, kindness, and respect for others in my Convocation speech. First lady Barbara Pierce Bush ’47 had also been invited to address students that day, and the audience was filled with dignitaries from across the state. I focused my comments on uniting our community. “Each one of us must accept the responsibility to expand our knowledge, respect others, and face the challenges that confront us,” I stated to an overflow audience in the newly built athletic center. Students cheered enthusiastically. Nobody wanted a repeat of the previous year.

With classes underway, a newly formed task force of students, faculty, and staff began meeting every week to discuss how to activate some of the ideas that had emerged from the events of the previous spring. One of the most powerful initiatives to grow from those meetings was the creation of a day of learning that could bring to life some of the elements of President Dunn’s Smith Design for Affirmative Action and Institutional Diversity. Developed in 1988, the document outlined several strategies for recruiting and retaining more students and faculty of color, integrating more diverse perspectives into the curriculum, and improving the overall campus climate by addressing issues of bias and discrimination, providing support to students of color, and promoting open dialogue on diversity-related topics.

This photograph also appeared in the May 4, 1989, special edition of The Sophian. The caption read, “Approximately 500 Smith students demonstrated their anger at a campus rally last Thursday over the most recent anonymous harassing notes found in Chapin House.”

Named for Otelia Cromwell 1900, the college’s first known African American graduate the day—which at the time was dubbed a “symposium”—was organized around the experience of racism and the ways in which one can turn negative into positive by learning, growing, and evolving. President Dunn began the inaugural panel by remembering Dr. Ng’endo Mwangi ’61, Smith’s first Black African student—in whose honor the Mwangi Cultural Center was named. In an interview with The Sophian, Dunn emphasized an important theme of the day: If racism is taught, it can also be untaught.

Overall, the first Otelia Cromwell Day was seen by the college as a welcome step toward healing the campus. Everyone from student leaders to administration officials wanted a new beginning, and the creation of a day of learning instilled a sense of pride that Smith was willing to do something bold and meaningful to build a stronger campus community. I’m happy to say that the inaugural symposium has blossomed into an annual tradition now known as Cromwell Day, in recognition of both Otelia Cromwell and her niece Adelaide Cromwell ’40, Smith’s first African American faculty member.

In 2025, it might not seem so audacious to propose a day dedicated to studying racism. But back in the late 1980s and early 1990s it was considered visionary, and its impact since then has benefited Smith in countless ways. As a campus, we witnessed how something so ugly and horrible could catalyze action and inspire us to strive for a better Smith. By working together, we were able to engage with hard issues and recognize that there is light even in times of darkness. Learning how to disagree and find ways to hear one another—even when it was painful—took practice, but it was worth the effort. That is not to say that we fixed everything. One day of learning about racism was not—and is not—a silver bullet. Smith continues to have challenges around racism, but we know as a community that we can navigate through those issues and come out stronger. As a former diplomat, I understand that these skills are part of the art of diplomacy. In order to bring about change and progress, you must be able to work with people who have different points of view.

As someone who has spent much of her professional life working on public and foreign policies that go directly to issues of identity and belonging, violent extremism and hate, I often look back on my Smith experience as a time of preparation and skill building, of practicing diplomacy, and of learning when to compromise—or not—on something that was seemingly nonnegotiable. The many lessons learned from the events leading to the creation of what we now know as Cromwell Day can be applied to the work of building a strong Smith community.

Of course, in 2025 there are layers of complexity that did not exist when I was at Smith. Students today are navigating a deeply polarized world. They must wade through misinformation and disinformation; civility and societal norms have been fractured; and there are dangerous domestic and global crises threatening the foundation of our democracy. What I would tell students today is this: It won’t be one solution that will spark change; rather, it will be many actions collectively. This requires hard work, but the way to build bridges, narrow divides, and create respectful, diverse communities is to find the strength to engage and build together. My classmates and I were bonded by our commitment to the power of Smith, our dedication to carrying forward the legacies of those who came before us, and our desire to be leaders who pioneered fresh ideas.

As Smith celebrates its 150th anniversary, we should be proud. Of course, Smith is not a perfect place; it never was. But it was created precisely because higher education in America was not perfect. A century and a half after its founding, Smith remains a remarkably powerful place. Transformational advances in how we learn, what we learn, and why we learn give Smithies extraordinary skills to compete and lead with courage, conviction, and vision. E. Shelton Burden’s description of my “trial by fire” was true—but those flames ignited in me something far stronger than I could have imagined.

Farah Pandith ’90 is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and the Muhammad Ali Global Peace Laureate. She served in the George H. W. Bush, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama administrations, most recently as the first-ever special representative to Muslim communities. She is a Smith College medalist and former SGA president.

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of the Smith Quarterly.