How Tammy Baldwin Wins in a Divided America

Smith Quarterly

The Wisconsin senator’s strategy isn’t flashy, but it works: Meet people where they are, listen to their concerns, and get things done

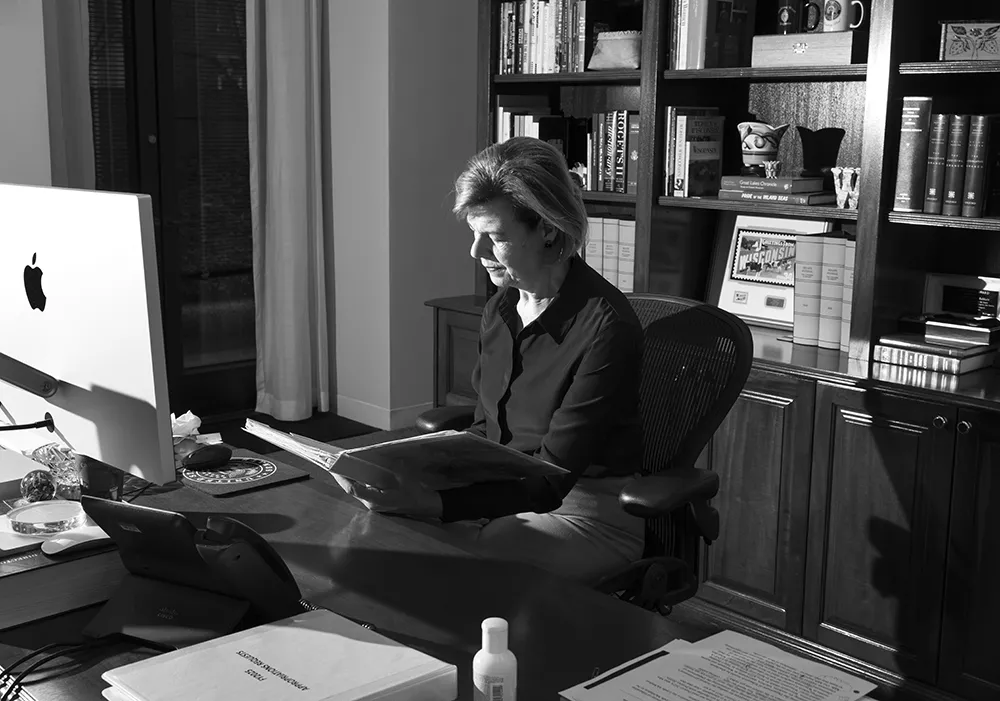

Photographs by Thea Traff

Published April 18, 2025

When Wisconsin Democrat Tammy Baldwin ’84 won her third U.S. Senate race in November, even Fox News wanted to hear from her.

Baldwin won by 28,781 votes—almost the exact margin that carried Donald Trump to victory on the same ballot. She outperformed Kamala Harris in 65 out of 72 Wisconsin counties. Statewide, around 4,000 more people voted for her than for Harris. “Trump-Tammy voters” were rare, but they were real.

During the campaign, Baldwin garnered support from the usual left-leaning groups—the Wisconsin State AFL-CIO, the Human Rights Campaign, the Planned Parenthood Action Fund—thanks to her progressive voting record. In a rare departure, she also became the first Democrat in more than 20 years to be endorsed by the Wisconsin Farm Bureau Federation in a statewide race.

“I think showing up matters, listening matters,” Baldwin told a Fox News Digital reporter in a postelection interview. “And so I go, and I really listen and get to know the challenges and aspirations of people all over the state: rural areas, suburban areas, urban areas.”

Baldwin is not on Fox News very often, or on any other major network. She keeps a low national profile. Sure, the media took interest when she made history in 2012 as the first openly LGBTQ+ senator, when Joe Biden reportedly considered her as a running mate in 2020, and when her 2024 campaign had the potential to determine the Senate majority. But outside of Washington and Wisconsin—and Smith—most Americans know nothing about her.

At the same time, nearly every American has felt the impact of her work. One notable example: Baldwin wrote the Affordable Care Act amendment that allows young people to stay on their parents’ health insurance until age 26.

Four days before the presidential inauguration in January, I met Baldwin, who is 63, at the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee headquarters, an inconspicuous building overlooking the U.S. Supreme Court on one side and the Hart Senate Office Building on the other. Washington was snow-covered and cold that Thursday afternoon, and 30 miles of black fencing lined the sidewalks in an inauguration security measure.

Like the Fox reporter, I wanted to understand Baldwin’s win and the lessons a weakened Democratic Party might draw from it. But I also wanted to know how she was approaching her work in the Senate now that Republicans had won the majority and how she planned to navigate the Trump administration. I was curious about her origin story, her motivations, and her take on the country’s profound divisions, too. After all, her career is proof that common ground exists in American politics.

“I think there are a couple of reasons why I won,” Baldwin said at the start of our interview. “My approach as both a senator and as a candidate is to show up everywhere, listen deeply, and then do my best to try to deliver. There are some Trump-Tammy voters out there who relate to that approach.”

The other main reason is her familiarity. “Kamala Harris had 107 days to introduce herself. And while she came to Wisconsin multiple times, that’s not a substitute for years of traveling the state and getting to know people—including many Republicans,” Baldwin said. “We’re a very divided state, so if I’m traveling everywhere, listening to the concerns of dairy farmers, people in the timber industry, people in manufacturing, I’m constantly meeting independents, Democrats, and Republicans. When you listen deeply and you then follow up, that can break through your partisan background.”

It’s a lesson she learned in middle school.

When Baldwin was growing up in Madison, Wisconsin, she and fellow members of the Van Hise Middle School student council formed a school-community relations committee. They went door to door, surveying the neighborhood with two questions: What do you like about living next to the school? And what don’t you like?

One neighbor was frustrated that students were trampling her tulips as they cut the corner on the walk to school. Another complained about a noisy air exchanger. A third was upset about kids smoking near her backyard.

“We took this input, and we went and solved each problem,” Baldwin recalled.

They installed a little fence to protect the tulips. They successfully lobbied the school board for a muffler on the air exchanger. They asked a patrol person to wave the smokers away. With every issue addressed, they invited the neighbors over for juice and cookies.

Show up, listen, deliver: Already, Baldwin had honed her approach.

Tammy Baldwin was raised by her maternal grandparents. Her parents divorced when she was 2. Her mother struggled throughout her life with mental illness, chronic pain, and addiction to prescription opioids, and her father was not in the picture. Baldwin’s grandfather, a biochemist, was a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her grandmother became chief costumer in the university’s theater department.

At age 9, Baldwin spent three months in the hospital with an illness similar to spinal meningitis. As she lay there, her grandparents learned that their health insurance did not cover grandchildren. Even after Baldwin got better, no company would provide a policy because she was now a child with a pre-existing condition.

“So, I grew up without insurance,” Baldwin said. “Fortunately, I was healthy thereafter. But between that and watching my mother’s struggles, I felt the system was broken and needed fixing.” These experiences would shape her career. “The issue that brought me to public life was health care,” she said. “I believe that everyone should have access to high-quality health care that they can afford.”

Baldwin was the valedictorian of her class at Madison West High School. She aimed for Harvard—but got waitlisted. “I went to Smith determined to apply to transfer,” she said. But within a few weeks, she’d fallen in love with the college: the competitive academics, the intimate class sizes, her fellow students, the access to faculty. “I never thought again about transferring.”

Baldwin double-majored in mathematics and government and was active in student government, representing Bedford Terrace as a student senator. She interned at the U.S. Department of Justice through Smith’s Jean Picker Semester-in-Washington Program.

One of her favorite professors was James Henle, now the Myra M. Sampson Professor Emeritus of Mathematics & Statistics. “He assigned us ‘insoluble problems’—problems with no solutions—as homework,” she recalled in the Commencement address she delivered to the class of 2009 at Smith. “Professor Henle’s point was that by pushing against the boundaries of what we knew, we could expand those boundaries.”

Baldwin came out at age 21, first to herself, then to her closest friends, she told the class of 2009. “The world was a lot different back then. So was Smith,” she said, pointing to “the fear of consequences—in class, at home, and on the job.” In search of role models, she learned about the gay rights movement. “I discovered a history of courageous people who took huge risks to gain a few more rights or change a few minds.”

Baldwin by the Numbers

The Basics

63

Baldwin’s current age

24

Age when elected to the Dane County Board of Supervisors, her first political office

7

Terms in the U.S. House of Representatives before becoming a senator in 2013

3

Committee assignments in the current Senate

Baldwin worried she’d have to choose between a political career and being honest about her identity. But at age 24, she said in her Commencement address, “I did one of the most terrifying things I’ve ever done. I gave an interview to my local newspaper. And I told them I was a lesbian. That spring, I was elected to the Dane County Board of Supervisors—anyway.”

Baldwin was a first-year law student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison at the time. She’d moved back right after her college graduation. “My grandfather had passed away between my junior and senior years at Smith,” Baldwin told me. “My grandparents were, when my mother went to college, empty nesters. They probably were thinking about a life of retirement, and then they get this little infant they raise until I go off to college. I wanted to be back, to give back to my grandmother. She was a widow. She was fiercely independent, but I wanted to be there for her.” (Later, after she’d started working in Washington, Baldwin became her grandmother’s caregiver.)

Baldwin served on the Dane County Board through law school and in the years after, until she ran for a seat in the Wisconsin State Assembly and became that body’s first open lesbian. In 1998, after six years in the state legislature, she set her sights on Washington.

Running for an open seat, Baldwin defeated Republican Josephine Musser, 53% to 47%, to represent Wisconsin’s 2nd District in the U.S. House of Representatives—becoming the first woman to represent Wisconsin in Congress and the first open lesbian in Congress.

Media coverage of Baldwin from that period focused on her status as an LGBTQ+ pathbreaker. (This is true of outlets ranging from C-SPAN to the Smith Quarterly.) Indeed, Baldwin’s win made her a role model in the queer community. And during her 14 years in the House and now 12 years in the Senate, she has worked to advance LGBTQ+ equality in the United States. But as she told the LGBTQ+ magazine The Advocate in 2013, Wisconsin voters she met during her first Senate race “almost never” asked about her sexual orientation.

“If anyone on the campaign was likely to raise the issue,” she told The Advocate, “it was typically a journalist.”

On election night in 2000, NBC News political reporter Tim Russert famously wrote on a whiteboard that the presidential race would come down to “Florida, Florida, Florida.” For Tammy Baldwin, every decision comes down to “Wisconsin, Wisconsin, Wisconsin.”

This was apparent during the presidential transition this year. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as health secretary? “Wisconsin parents don’t want their kindergartners coming home with mumps or measles,” Baldwin said in a press release. The pause on federal grants? “I met with and heard from Head Start programs across Wisconsin about the devastating impact the unlawful federal funding freeze had on their individual programs and in our communities,” she wrote. The ban on trans girls in sports? Wisconsin sports associations don’t need the federal government butting in. “While Republicans are laser-focused on playing politics with kids’ sports leagues,” she announced, “I’m focused on the issues I hear about from Wisconsinites—lowering costs at the pharmacy and grocery store; getting people good, affordable health care; and keeping the Badger State safe.”

Wisconsin, Wisconsin, Wisconsin.

When I asked about her off hours, Baldwin gave similarly Wisconsin-centric answers. During Senate breaks, her home base is in Madison, where she sews, completes DIY projects (many involving carpentry), and grows herbs, vegetables, and flowers in planters on her deck. She also uses that time to meet with constituents, which means she does a lot of driving all over the state.

Making History

1st

Open lesbian to serve in the Wisconsin State Assembly and U.S. House of Representatives

1st

Openly LGBTQ+ person to serve in the U.S. Senate

1st

Woman to represent Wisconsin in the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate

64

Women to ever serve in the Senate, out of 2,018 senators total (Baldwin is the 40th female senator)

The name “Wisconsin” originates from “Meskonsing,” the Miami Native American word for the river that runs through the state. It means, “This stream meanders through something red.”

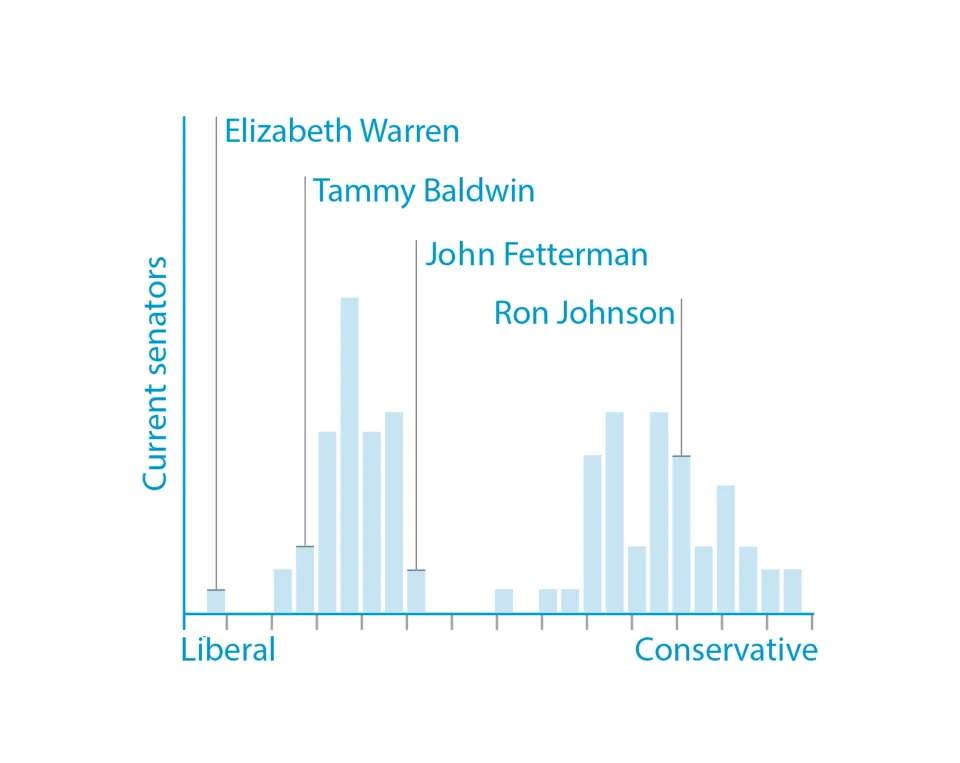

That likely refers to red sandstone, but politically, the river meanders through something purple. Wisconsin has a nearly even mix of red and blue voters. The past three presidential races in the state have been decided by a fraction of a percentage point. Today, Wisconsin is one of only three states represented by a split ticket in the Senate. (The others are Pennsylvania and Maine, and three is the lowest number since Americans began directly electing senators in 1914.)

It’s “the land of the nail-biter,” said Ben Wikler, chair of the Democratic Party of Wisconsin, at Steamfitters Local 601 in Madison on election night in November. In the victory speech that followed, Baldwin outlined her strategy for working with the new administration. “You know that I will always fight for Wisconsin,” she said, “and that means working with President Trump to do that and standing up to him when he doesn’t have our best interests at heart.”

Baldwin thanked dairy farmers, LGBTQ+ families, women, the labor movement, and foundry workers in her speech. She talked about championing the “Buy America” reform that Trump signed into law in 2018, which requires federally funded water infrastructure projects to use American-made iron and steel.

This was key for at least one Trump-Tammy voter. Baldwin met him on a foundry tour during the first Trump administration, and he asked her, “Why do you keep picking on my guy Trump?” After the tour, a member of her staff asked the man what he thought of Baldwin.

“If it weren’t for her Buy America work, I wouldn’t have a job,” he said.

Baldwin told me that most of what the foundry produces is for water infrastructure—manhole covers, grates, and the like. “If there weren’t Buy America rules—well, you can source those things much more cheaply in countries that have an unlevel playing field,” she said.

Baldwin met another Trump-Tammy voter when he hosted a roundtable at his dairy farm. As Baldwin recalled, a reporter noticed a Trump sticker on the farmer’s car and asked what he thought of Baldwin.

The farmer said, “I’m a big supporter of Tammy’s.”

He praised her efforts to help dairy farmers, and the Wisconsin Farm Bureau did the same in its endorsement of Baldwin, citing two such efforts: expanding a U.S. Department of Agriculture program that provides technical assistance and grants for dairy businesses to develop new products, and introducing, as part of a bipartisan group, a 2023 bill that would have required any product marketed as milk, yogurt, or cheese to actually be made from dairy.

Milk from a cow, not from an almond: That matters to Wisconsinites.

What makes an effective senator? The most important factor is to win reelection, says Smith Assistant Professor of Government Claire Leavitt, who studies legislative institutions, partisan polarization, and the role of gender in legislative behavior. She points to research showing that the longer someone serves in Congress, the more they get done. Seniority is the path to a leadership position and to a seat on the key committees—and, in turn, to direct influence over legislation.

Senate reelection is no easy task. Compared to House races, the campaigns cost more money and attract stronger challengers. “So a big part of a senator’s job—especially in a swing state—is to go back home and inculcate trust,” Leavitt says. “There’s a tradition in the Midwest, and specifically in Wisconsin, where members, if they inculcate trust, can take iconoclastic or slightly unpopular votes. People will say, ‘I don’t agree with you on this, but you seem like you have your head on straight.

Baldwin is now in her 26th year on Capitol Hill. She is part of the leadership—as secretary of the Senate Democratic Caucus—and serves on arguably the most powerful committee in the chamber: the Appropriations Committee, which has enormous influence over federal spending.

“Getting on a committee like Appropriations means you have control over the U.S. government’s budget,” Leavitt explains. “And that means you can insert provisions into legislation that funnel money to Wisconsin. You can credibly claim that this research laboratory was funded, or this factory didn’t close, or—insert your pet project here—that this is because of the work you’ve done.”

Even so, how effective can Baldwin actually be, given today’s 53–47 Republican majority? “In the Senate, it’s not as dire as it would be in the House,” Leavitt says. “If you’re an individual member of the House of Representatives in the minority party, forget it; you can take a seat for two years. Individual senators, though, still have a lot of power.” The main reason is that most Senate legislation requires 60 votes to advance. In the current Senate, Democrats from red and purple states will be key targets for bipartisan negotiations. “In that regard,” Leavitt says, “I think she’s in a far better position individually than her safe blue-state colleagues.”

As Baldwin pointed out, crossing the aisle works both ways. “I know that if I’m going to get a bill passed, I need bipartisan support,” she said. “When I’m serious about getting something done, I’m always looking to my Republican colleagues. And I think that means you can then run a campaign that reaches out to people of all ideological perspectives.”

However, even Senate rules can’t mask how divisive politics has become. “When I was in the state legislature, before I was elected to Congress, we argued in session and then went out to dinner together,” Baldwin recalled. “I think about why many of these changes have occurred. I think part of it, in Congress, has to do with the fact that there is no longer much time taken to socialize with people of even your own party, but certainly not members of the other party. People are trying to get onto Fox News or MSNBC, you know what I mean?”

And when they do—well, cable news is not the best place to seek common ground. “I think people have said some things they can’t take back; maybe they’ve said those things so they can get booked again,” Baldwin said. “But if you say harsh words about a colleague, you can’t unsay them the next time you see them in the hallway.”

A Divided State in a Divided Nation

0.9%

Baldwin’s winning margin in the 2024 Senate election

0.8%

Donald Trump’s winning margin on the same state ballot

90%

Wisconsin counties in which Baldwin overperformed Kamala Harris

3

States currently represented by a split ticket in the Senate (Maine, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin)

4

States that chose Trump for president and elected a Democrat to the Senate in 2024

Baldwin’s years in politics have brought other changes, too. Among them is the number of women in Congress. In 1999, when Baldwin joined the House, there were nine women in the Senate and 56 in the House. Today, there are 26 women in the Senate and 125 in the House.

One is U.S. Representative Becca Balint ’90, a Democrat in her second term representing Vermont’s at-large district. Like Baldwin, Balint is the first woman and first LGBTQ+ person elected to Congress from her state. “Many people say it isn’t possible, until it happens,” Balint told me by email. “Senator Baldwin has shown so many women and girls in Wisconsin and across the country that your dreams are within reach.”

Women are still vastly underrepresented. Research by a leading expert on women in politics, Jennifer Lawless of the University of Virginia, shows that female Congressional candidates win elections at the same rate as their male counterparts. The problem is that women are less likely to run.

“When I talk to my students, I ask how many of them want to run for office someday,” Leavitt says. “One or two hands will go up. I then ask why they don’t want to run. They say, ‘They’ll comb through everything you’ve ever done, any picture you’ve ever sent, anything you’ve posted, and they’ll destroy your life.’”

This is of great concern because, as Leavitt notes, when women serve in Congress, legislation becomes more female-focused. As an example, she points to the Affordable Care Act’s requirement that health insurers cover mammograms as preventive care.

Baldwin, of course, became interested in politics because of health care. Indeed, one of her proudest achievements is her work on the Affordable Care Act. As a member of the House committee that wrote the 2010 act, she offered the amendment that requires health insurers to allow those younger than 26 to remain on their parents’ plan. “It was a game-changer for so many young people,” Baldwin said.

Women Are Underrepresented in the Senate

3.17

Of all U.S. senators have been women

26%

Of current senators are women

The greatest disappointment of her career came after the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade. “Half of America now has fewer rights than their mothers and grandmothers had,” Baldwin said. “I’ve heard the stories of suffering because of lack of access to health care, and it’s horrendous. So, one of my disappointments is not having restored those rights.” Long term, she has hope for federal legislation. “It’s not going to happen in the short run, but we’ll organize for the day that it will.”

Our time almost up, Baldwin needed to get to her next meeting, which was with Lieutenant General Tony D. Bauernfeind, superintendent of the U.S. Air Force Academy. Already that day, she’d met in her office with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. She’d spent time with the nominee for labor secretary, Lori Chavez-DeRemer, and with the mayor of Milwaukee, Cavalier Johnson. She’d talked to a Washington Post reporter. She’d taken part in a caucus lunch, during which Democrats had strategized about how to more effectively use social media.

Before long, Baldwin would visit the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where, as the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel would report, she’d say that the first few weeks since Trump’s inauguration were “looking more like a coup than a transition.”

But for now, Baldwin put on her puffy winter coat, crossed the street, entered the Hart Building, and walked into her office, ready to continue her work as one of two senators representing Wisconsin and one of 100 charged with supporting and defending the Constitution of the United States.

Emily Gold Boutilier is a writer and editor based in Amherst, Massachusetts, and a former editor in chief of Amherst College alumni magazine.