Art As Sanctuary

Smith Quarterly

A poet, a hurricane, and a night alone in the woods

Illustration by Laura Weiler

Published November 17, 2025

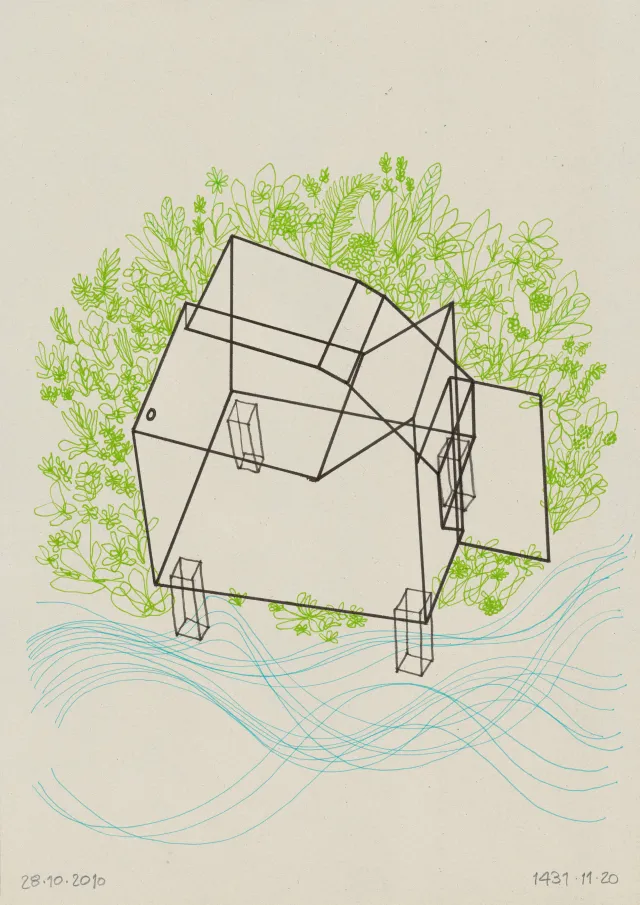

Friday, September 27, 2024—Deep in the woods of Whately, Massachusetts, moonlight discovered what looked like a ship wrecked far from the sea. An installation by the internationally acclaimed Moroccan artist Younes Rahmoun, the sculpture borrowed its structure from the space beneath the stairs of Rahmoun’s childhood home, an ocean away in Tetouan, at the foot of the Rif Mountains. Rahmoun’s mother had cleared the space and offered it to him as a ghorfa, a room, of his own. With this gift, a young artist had his first studio—and, in a crowded house, a refuge.

Nearly three decades later, Rahmoun had built 13 of these ghuraf around the world, each with the identical dimensions of the space beneath the stairs but with an exterior that incorporated materials native to their location. At Smith’s MacLeish Field Station—a combination environmental classroom, laboratory, and arts space—Ghorfa #13 (Al-Ana/Huna) or Room #13 (Here/Now) was inspired by the Lyman Plant House & Conservatory at the Smith botanic garden. Framed in wood, its walls are windows and its roof is sheets of corrugated, translucent plexiglass. A transparent enclosure, it allows you to be both inside and out at once, providing shelter while framing the woods beyond it, revealing each view as its own work of art.

Far to the south, just after midnight, Hurricane Helene made landfall. Laying waste to miles of salt marsh and pine flats on the Florida Panhandle, spawning tornadoes and record-breaking storm surges in its wake, it was about to be the deadliest storm on the U.S. mainland since Katrina. It seethed north, making an unexpected path toward the Carolinas.

I’d learn later that while I spent the night in a work of art, a once-in-a-thousand-year flood was devastating my town.

In my town of Asheville, North Carolina, it had been raining for days. Run-off from an earlier storm had swelled the river that runs through the city, loosened the steep soil of the Blue Ridge Mountains, and, early that Friday morning, sent a maple crashing down on the deck of my partner’s home, its massive crown resting against the house. Other trees sprawled behind her car, boxing it in. I wasn’t there. Instead, I was in Northampton, scheduled to teach a writing workshop that evening.

As a former English major at Smith, I’d been honored to return there to give poetry readings and teach, and this workshop had been a joyful event on the horizon. Now all I could feel was regret at being gone. I gazed out the window of my hotel room at a clear sky as we spoke, searching for a way to help. Even if she could have driven away—even if I canceled the class, left immediately, and headed south—flooding had closed all roads in and out of the region.

Muddy water began cascading down the surrounding hills, through the side door, and into the hallway and kitchen. She stood alone on the threshold for hours, bailing with a small trash can. During a break, she called and reassured me that the rain had let up. “I’m going to take a walk and see how bad it really is,” she said, her voice crackling over the weak line. “Have a great workshop tonight. I’ll be OK.”

“I love you,” I said, but wasn’t sure if she heard me.

Rahmoun built Ghorfa #13 (Room #13) at Smith’s MacLeish Field Station in Whately, Massachusetts.

Photograph courtesy of the artist

I ran along a road that spooled out through Easthampton’s Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary, protected land in a sprawl of fields and paths beside an oxbow of what was once river. Beneath tufts of clouds lifted from a pastoral painting, I ran toward the surreal blue horizon. The crush of gravel was pleasing underfoot, and I tried to give myself to its sound, to lose myself to movement. Yet each time I passed the sign “Arcadia,” I could think only of Greek myths and far-off utopias: A lost, unattainable paradise. Back at the car, I called to check on her, and the call went straight to voicemail. Local news reported power outages across the county. All the lines were dead.

A few weeks before, we’d sat together on the deck beneath a sweltering sky, thankful for the shade cast by the maple. It was my first time applying for the Guggenheim Fellowship, a mid-career award for practitioners in every field of knowledge and art form, from poets to astrophysicists. She kindly paused her own work throughout the day to offer feedback on my drafts. I tried not to sweat on the keyboard.

Though I’d recently published my third collection of poetry, unalone—poems in conversation with the Book of Genesis—the whole thing felt like a long shot. Writing that book, which required an intensive study of Jewish texts, had inspired me to found Yetzirah: A Hearth for Jewish Poetry, the first and only national organization devoted to supporting Jewish poets. While this work felt increasingly vital, running Yetzirah meant little to no time for slowing down enough to write. My own poetry was far from me. Still, I told myself as I stared up at the tree, this was a good exercise—the application a way to look back and take stock in order to better look forward. For the required statement of plans, I noted I’d been commissioned by the Smith College Museum of Art, The Boutelle-Day Poetry Center, and the Arts Afield program of the Center for the Environment, Ecological Design, and Sustainability to write a poem responding to Ghorfa #13 and teach an ekphrastic workshop.

What was it, I wondered, that drove Rahmoun to keep re-creating variations of the same remembered structure? Writing unalone, I’d become fascinated by the story of Jacob’s wrestling match beside a river at night. In some tellings, his partner is an angel or even God. In more contemporary interpretations, on that dark night of the soul, the one he wrestled was himself. When I accepted the commission, I made one request: After the workshop, I wanted to sleep in the artwork to know it by night, to grapple with whatever might arise.

Beyond the large windows of MacLeish, dusk dimmed the sky. Twelve Smith students leaned in around the table, describing a work of art that had moved them: Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon linked one student to her lineage, and The Nutcracker was another’s trapdoor into childhood; when one needed a moment of discernment, she listened to a Moroccan song with the lyric, “What will you do with your life?”

“Did you notice,” I asked, “how you didn’t just mention the art but the memories and emotions it evokes in you?” Art is a mirror we can revisit throughout our lives, noting in its reflection how we’ve changed—and, in that changing, we can in turn know the art, and ourselves, anew. This new knowing was why we were there: Ekphrasis, I explained, is from the Greek ek, “out,” and phrazein, “to explain.” So, ekphrastic writing enters into conversation with work in another medium, calling out to a piece of art and letting it sound its call in you.

Then we took a winding walk through the darkening woods. One student said she’d come there before with an art class but couldn’t find Ghorfa #13—“and we’d had the artist there with us!”

So many lost, unattainable paradises, I thought, but said instead, “Imagine what it might be like to share the private space that formed you in such a public way. To take what you carry inside and rebuild it again and again for others to inhabit, take from it, and make of it what they will. The power and vulnerability of that act.”

Thankfully, we found the right path, and the students were raucous as they walked toward the installation’s door. But then, without discussing it or seeming to make a conscious choice, each fell silent as soon as they entered.

Walking around the clearing, checking on students perched on rocks and leaning against trees to write, two thoughts looped in my head: Is she OK? Please let her call soon.

Later, when I returned to the ghorfa alone, the walk felt much longer. Unseen creatures crashed through the leaf litter, and the barbs of skittering porcupines gleamed in the beam of my headlamp. Twice, I got lost and had to backtrack. Finally stepping into the ghorfa, stooped by its low roof, I placed my shoes beside the entrance, rolled out my sleeping bag, and set out a book and my journal—arranging everything just so, as though external order could transfer inside. As soon as I lay down, Asheville’s relentless rain found the ghorfa’s roof in soft drops.

I’d learn later that while I spent the night in a work of art, a once-in-a-thousand-year flood was devastating my town. Cresting nearly 25 feet above its normal level, the French Broad River that runs through Asheville exceeded its banks by the length of three football fields, flowing with enough force to unmoor entire buildings and carry them away in its current. The nearby Watauga, Catawba, and Swannanoa rivers all reached near or above their previous record flood levels. In the end, 108 people were killed in North Carolina alone, Asheville’s River Arts District was decimated, whole towns were destroyed, and countless livelihoods and homes were lost.

But in that moment, I knew only that the person I loved was alone in a place of rushing water and falling trees. What if another had fallen while she was outside? I opened the book, but the words were blurred. My mind wrestled with itself. What if she was hurt and couldn’t call for help? The rain on the roof intensified. I opened the book’s blank back page and scrawled, “Maktub, Muslims say when accepting fate: ‘It is written.’ But what do the words say? What has been lost, and what will continue?”

I slept little and left at first light.

At the end of the last of the 13 poems I’d go on to write about Rahmoun’s art and my experience of it—one poem for each of the ghuraf he’d created—I wrote:

Before leaving, I took the room’s

whisk broom with no handle and bent

to clean. A protocol to convince

myself as much as the God in whom

I’m not sure I believe

that I accepted what I couldn’t

control—not knowing, in a few hours,

I’d hear her voice, again,

alive, or that part of me

would continue to live in the in-between

of that temporary shelter, that offering

that now lives in me, place of the possible

As we met up again with great relief in Wilmington, North Carolina—where we held each other and wept, where we loaded up on supplies and donations before driving back to Asheville—there was so much we couldn’t yet know. The power in homes throughout the area would be out for over three weeks, the pipes would be empty for nearly a month, and we would be without potable water for two. We’d drink from friends’ wells and haul water from the nearby creek to flush toilets and wash dishes. Businesses—many still paying off pandemic loans—would fold after being shuttered during tourist season, and, nearly a year after Helene, many hiking trails would remain closed due to landslides that were secondary effects of the storm. We’d end up volunteering for a nearby river town whose main street was coated in toxic mud after the factory upstream was flooded.

What was the point of writing a poem when I could distribute supplies, carry water, or help cut back a fallen tree?

Yet one thing during that time was all too clear: Poetry felt further from me than ever. What was the point of writing a poem when I could distribute supplies, carry water, or help cut back a fallen tree?

But as I watched the widespread mutual aid and witnessed neighbors—even those who’d suffered great losses—do all they could for each other, I thought of the ghorfa Rahmoun carried inside. It wasn’t enough for him just to remember it. He was moved to offer this refuge to strangers.

In March, six months after Helene, I sat on the couch of what was now our shared home, looking out at the open sky where the maple had been. I’d just received an email I had to read three times before I could believe what it said: I’d been selected as a member of the 100th class of Guggenheim Fellows. A message of affirmation, inspiration, and imperative.

Compared to so many, we’d been lucky during the storm. But each day spent gingerly stepping over downed power lines on our way to the creek, each evening eating dinner by lantern light, gazing out the window at an unlit street, had been a visceral reminder that so much of what we take for granted can be taken in an instant.

Yet on my own darkest night, I’d found sanctuary in a work of art. Younes Rahmoun had built the heart of his home in the heart of a forest, and, within it, allowed me shelter. And now, 20 years after Katrina, and one year after Helene, I search for ways to create on the page a version of what Rahmoun constructs in the world. An ark for when the waters again begin to rise, a wisdom-built refuge. What resources do I, do you, carry inside, and how might we share them.

Jessica Jacobs ’02, a 2025 Guggenheim Fellow, is the author of unalone (Four Way Books, 2024) and Take Me with You, Wherever You’re Going (Four Way Books, 2019), both named one of Library Journal’s best poetry books of the year; Pelvis with Distance, a biography-in-poems of Georgia O’Keeffe (White Pine Press, 2015), winner of the New Mexico Book Award in poetry and a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award; and co-author of Write It! 100 Poetry Prompts to Inspire (Spruce Books/Penguin Random House, 2020). She is the founder and executive director of Yetzirah: A Hearth for Jewish Poetry.