All for the Cause

Faculty

A fighter with a big heart, Loretta Ross is here to build a more just future with all those willing to put in the work alongside her

Photograph by Peyton Fulford/The New York Times/Redux

Published September 21, 2023

Professor Loretta Ross is being inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame on March 5, 2024.

On a sunny Wednesday afternoon late in the spring semester at Smith, Professor Loretta Ross’ class on reproductive justice is just ending for the day. The day’s lesson focused on the ugly and vicious ways that the lack of reproductive freedom plays out in carceral settings. It takes Ross a little while to make her way through the animated gaggle of students, each of whom has one more question to ask or observation to make. There is plenty of laughter too. Though the class wrestles with tough subjects, Ross doesn’t let despair take over.

Arthritis has slowed Ross’ gait and made it necessary for her to use a mobility scooter around campus. “I didn’t get the self-care memo like these kids do now,” she says later, without any hint of bitterness. “I gave it all to the cause.” Her teaching assistants are on the job both in class (for the inevitable Zoom glitches) and out (for anything she needs). Still laughing and joking, one of them helps Ross wrestle with the scooter. As Ross settles into its seat, one of her long dreadlocks falls across her face and the student briskly, lovingly flicks it aside. Ross smiles and thanks her. This brief yet deeply affectionate moment tells you a lot about how Loretta Ross—considered one of the country’s most powerful voices for women’s rights—moves through the world. Not only is she tough, but she is also present, engaged, caring, incisive, and beloved. A fighter with a big heart, she is here to build a more just future with whoever is willing to put in the work alongside her. She keeps her eyes on the prize, always.

Photograph courtesy of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

The prize that is most immediately in her sights these days is one that has the potential to profoundly impact Smith, its students, and scholars for generations to come. Working alongside Carrie Cuthbert, project adviser and research associate in the study of women and gender at Smith, and Andrea Stone, associate professor of English language and literature, Ross is developing the Smith College Institute for Human Rights and Democracy, a far-reaching, curriculum-based initiative that is rooted in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Crafted in 1948, the UDHR laid out for the first time the fundamental rights to be protected and enjoyed by everyone, not by governmental edict but simply by virtue of being human.

The institute’s curriculum will pay particular attention to how these rights play out (or don’t) in the United States. Why the U.S.? “Because of our disproportionate power and significant noncompliance,” Ross says.

In keeping with Smith’s standards of academic rigor, the institute will include community-wide events, cross-disciplinary courses, and opportunities for public service. “Students will be prepared to be leaders, using the advantages of Smith to become fighters in leading for human rights change in the world,” Ross says.

For Ross, framing the institute and its curriculum around human rights as defined by the UDHR—rather than, say, social justice—offers a broader framework that can support long-lasting and sweeping change. “Human rights have a set of standards that grow from the declaration,” she says. “Social justice has many of the same ideas but without the architecture to enforce those rights.”

What’s more, Ross says, there is no academic discipline that doesn’t have human rights implications associated with it. Human rights “touches everything,” she says. “The way I teach it is that every human being has the same rights, but our identities tell us what our vulnerabilities are. That’s the purpose of intersectionality. What are you vulnerable to based on your identity that someone without that identity is not vulnerable to?”

For her part, Cuthbert envisions the institute as an “exciting laboratory” bringing together scholars and students from across the five colleges in the Pioneer Valley to develop innovative scholarship that expands the concept of human rights. Ross, she believes, is the perfect person to lead this effort. “In all her classes and in growing this project, she’s teaching life skills and human rights skills that can be transformative,” Cuthbert says.

Transformative activism is nothing new to Ross. She has been and remains at the forefront of nationwide movements for racial justice, civil rights, women’s rights, and reproductive justice. In the fall of 2021, for example, she joined other women in testifying before the House Committee on Oversight and Reform about the need for women’s continued access to health care and reproductive rights. Earlier this year, in an essay for Ms. magazine, she and co-author Anu Kumar called for a global framework for protecting and enforcing reproductive rights. “For everyone everywhere to be able to determine their own sexual and reproductive health, we must address the social, economic, and political barriers to accessing care,” they wrote.

This kind of passion, expansive thinking, and experience on the front lines of social change was what inspired then-Smith President Kathleen McCartney to invite Ross to serve as an activist-in-residence on campus in 2013. In that role, Ross delivered public lectures (her first was titled “Feminism in the Service of White Supremacy”) and conducted workshops that taught students the basic skills of organizing for social justice. Her presence on campus was so powerful and well-received that she was invited back in 2019 as a visiting associate professor. Then, in 2021, she was awarded tenure as an associate professor of the study of women and gender.

Ross’ professorship is the culmination of a long relationship with Smith, one that didn’t begin in academia. About 15 years ago, Sherrill Redmon, then the director of the Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History, and Joyce Follet, who directed the Voices of Feminism oral history project for the Smith College Archives, interviewed Byllye Avery, the founder of the National Black Women’s Health Project, for the Sophia Smith Collection. Avery suggested that Redmon and Follet also interview Ross. Follet approached Ross about participating and also donating her papers to the archives. Initially, Ross was reluctant. She wasn’t familiar with Smith and feared that she wouldn’t have access toher papers if she donated them. “I had a very visceral reaction,” she recalls. Redmon and Follet assured Ross that her papers would be digitized and that she would have full access to them at any time. Ross eventually conceded, donating most of her materials to the archives and sitting with Follet for an interview that resulted in a 364-page document (with a companion video) that outlines Ross’ life in granular, often harrowing, detail.

Born in 1953 in Texas, Ross was the sixth of eight children. Her mother, Lorene, owned a music store and was a domestic worker before becoming a stay-at-home mother. Her father, Alexander, spent time in the military before beginning a career with the U.S. Postal Service. From a young age, Loretta excelled at academics, crediting the military schools she attended while her father was in the Army with instilling in her a love of learning.

Ross’ preteen and teenage years were marked by two events that would alter the course of her life and, in part, inspire her activism as an adult. At the age of 11, she was beaten and raped by a stranger. Four years later, she experienced the same trauma at the hands of a distant relative. Her son, Howard (who tragically died of a heart attack in 2016), was born of that rape. Because Ross refused to place him for adoption, she lost a full scholarship to Radcliffe College, so she went instead to Howard University, the legendary historically Black research university in Washington, D.C. Although she says she received a stellar education while there, her experience was marred by misogyny and sexual harassment. “I had to hit a calculus professor with a pool cue because he told me the only way I could pass his class was to sleep with him,” she remembers. “I was 18 years old. I swung it at his head because I’m a rape survivor and that just hit me all wrong.”

“My mother had to clean white folks’ houses on her hands and knees so that I could be in this position to have this voice and use my privilege.”

Ross persisted at Howard for a few years before leaving to begin her work as an activist, drawn by the Black Power movement. Sadly, at 23, she once again experienced a form of sexual violence. Specifically, she was given a Dalkon Shield, a type of IUD that was known to have grave medical consequences. In Ross’ case, she developed severe pelvic inflammatory disease—after having been initially misdiagnosed with a venereal disease—and ultimately had to have a hysterectomy before she was 25. She became part of the first class-action suit against A.H. Robins, the manufacturer of the Dalkon Shield, asserting that if she had been correctly diagnosed to begin with, she never would have, in her words, lost her reproductive organs.

All of these abuses have caused immense pain and taken a toll on her psyche (she has said, for example, that she remembers little about her life between the ages of 11 and 14), but Ross also found a way to, if not transcend the pain, turn it outward and use it as fuel to fight for justice. Consider her many accomplishments and the influence she has had on political movements, women’s rights, and anti-racism work. She was one of the first African American women in the country to run a rape crisis center in the 1970s, in Washington, D.C. She launched the Women of Color Programs for the National Organization for Women in the 1980s. She helped found the National Center for Human Rights Education. She was the national coordinator of the Sister-Song Reproductive Justice Collective from 2005 to 2012. She was one of 12 Black women who created the term “reproductive justice” by splicing together “reproductive rights” and “social justice.” Coining the phrase “reproductive justice” was a particularly important achievement because it gave credence to the many circumstances that influence decisions about childbearing and rearing (class, race, security, or insecurity) that are often overlooked in the traditional binary view of pro-life or pro-choice. The list of her other accomplishments is far too long to enumerate here. When asked about her legacy, she simply says, “Oh, my legacy is already so firmly set. I’m not worried about that.” It’s impossible to disagree.

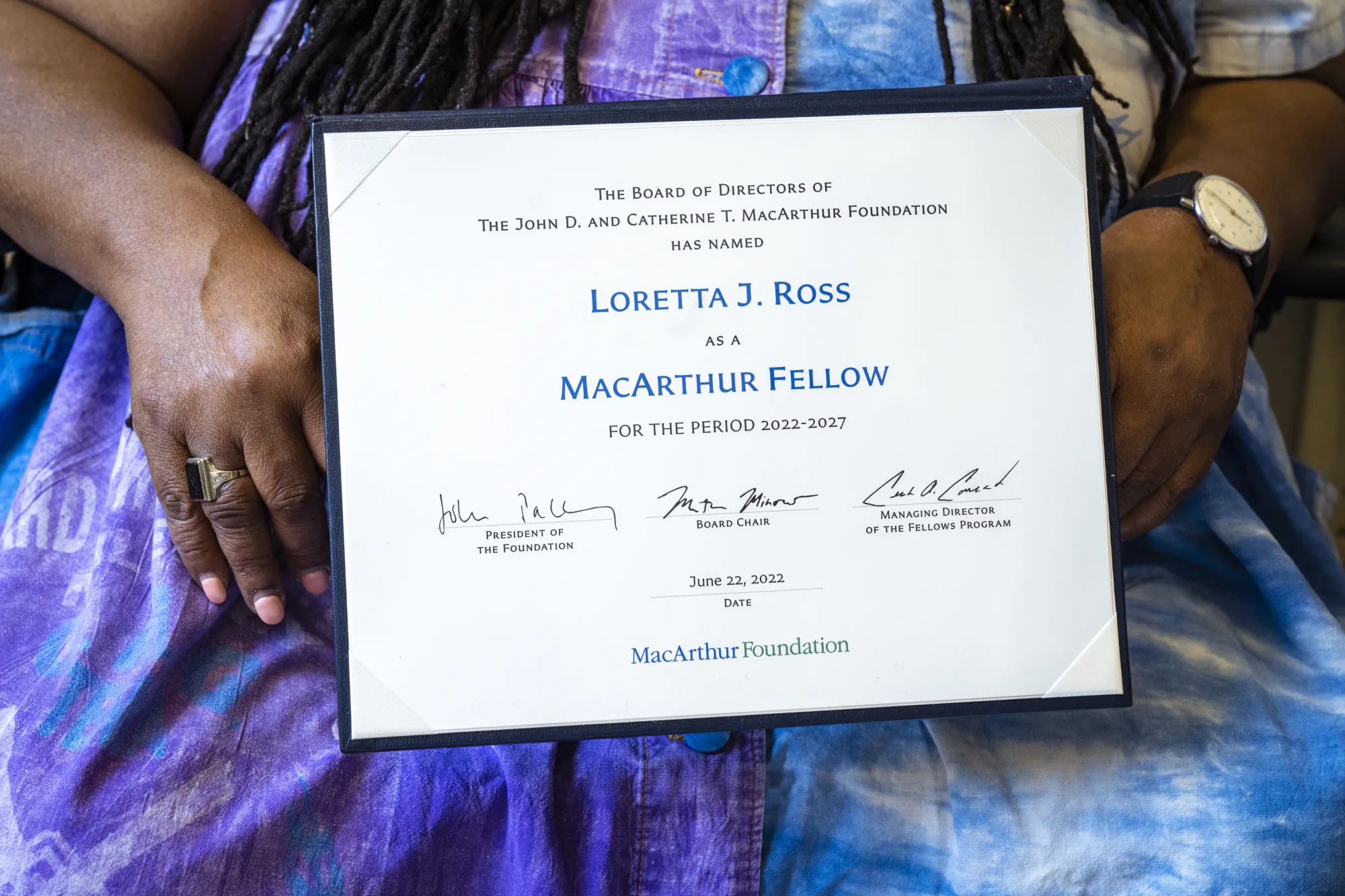

Upon accepting the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship in 2022, Ross said, “I am honored to receive this award to further the work of social justice.”

Photograph by Vanessa Leroy

In 2022, the MacArthur Foundation took note of Ross’ decades of leadership by naming her a MacArthur Fellow, a distinction that comes with a no-strings $800,000 grant, much of which Ross intends to use to help fund the human rights institute at Smith. As far as Ross is concerned, everything she is doing upholds a sacred duty. To be honored for her work is nice—but she’d do it anyway. “My mother had to clean white folks’ houses on her hands and knees so that I could be in this position to have this voice and use my privilege,” she says. “So I’m honoring my mama and all my ancestors when I choose to educate white people because I’m saying stuff that would have gotten her lynched.”

In recent years, Ross has gained even more national prominence for creating an antidote to what has become commonly known as “cancel culture.” Ross’ goal, by contrast, is to create a culture of “calling in” rather than “calling out,” as she terms it. She has taught the topic at Smith and elsewhere, and in August 2021 she delivered a popular TED Talk on it. Next year, she’ll release a book, published by Simon & Schuster, tentatively titled Calling In The Call Out Culture. Her argument, crystallized in an essay she wrote for The New York Times, is this: “Call-outs make people fearful of being targeted. People avoid meaningful conversations when hypervigilant perfectionists point out apparent mistakes, feeding the cannibalistic maw of the cancel culture. Shaming people for when they ‘woke up’ presupposes rigid political standards for acceptable discourse and enlists others to pile on. Sometimes it’s just ruthless hazing.”

Characteristically, Ross’ teaching doesn’t hew to orthodoxy on either side of the political divide. Rather, she’s interested in the truth. When the students in her White Supremacy in the Age of Trump class begin to conflate libertarianism with conservatism, she’s quick to remind them that “libertarians’ unifying concept is anti-government. They’re on the right, left, and center. It’s important to be precise about which sector you’re discussing.” Later, she says to me, “I want [my students] to get exposed to a wide range of things to read in order to form their own opinions. I give them what I call the ‘go behind the article’ strategy: Examine what else the writer has written so that you’re not just getting this glimpse of them but you see the range of their thinking. See not only who the writer is but who they are to say it.” In other words, learn to look deeper, the way an effective leader must.

Ross loves Smith and is grateful to be here. After she tells me about the Howard professor who tried to assault her, she says, “If I had a daughter, I’d send her to Smith.” She is particularly grateful to be spending what is likely the end of her professional career lifting up the next generation of scholars. “When I retired from SisterSong in 2012, I wrote a sticky note to myself and I said, ‘I want to teach, talk, and write.’ Because I knew, at 62, I’ve got a limited number of years left in this body. So how does it go for the last third of your life?”

As busy as she is creating a better world, she’s not out there fighting 24/7. On her website is this personal statement: “Loretta is a mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother. … She is an avid pinochle player, competing in tournaments across the country because this is how she balances her activist life with apolitical hobbies.” For her, joy is just as important as work.

Though Ross has a pied-à-terre in Northampton, she spends most of her time in Atlanta, where she has a “wonderful geriatric senior citizen community that is politically diverse and fun as hell,” she says. “We play pinochle together, and we sit around reading funeral programs like they are Hamilton playbills. ‘What did she have on in the casket? How did her grandchildren act? How was the preacher?’ We take cruises together, go to casinos together—just have a natural ball living out the last vestiges of our lives with no shame, no regret.” She calls her group of friends the Coalition of Smutty Crones. The name elicits a hearty laugh. Loretta Ross has come through fire—but it didn’t burn her heart, it just lit her way.

Martha Southgate ’82, a frequent contributor to the Quarterly, is the author of four novels, most recently The Taste of Salt.